What we know about protists mostly stems from the fact that they are common parasites and cause some of the most deadly diseases on Earth. Malaria, the most prominent, kills millions of people in tropical regions annually. Other well known diseases caused by protists include African sleeping sickness, leishmaniasis and Chagas disease.

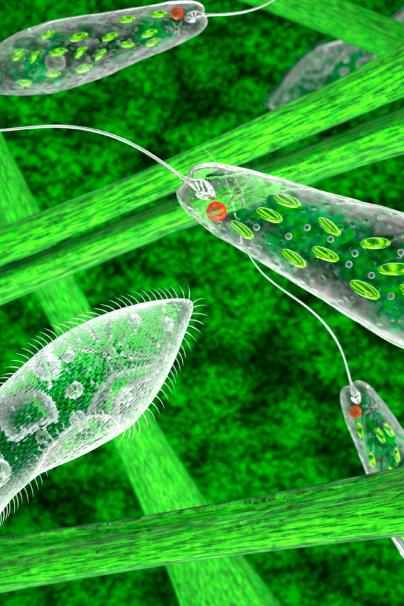

African sleeping sickness and Chagas disease are both caused by Trypanosomes, which Ross Low of the Hall Group at EI is interested in for reasons other than how devastatingly awful they are. These protists belong to the Kinetoplastid group, which are evolutionarily bizarre.

They’re not bizarre because of what they look like, like the real-life protist Kraken, Kraken carinae (I dare you to look it up, it’s actually called that). They’re bizarre because of their unique genetics and how their genes are expressed in large blocks, in what’s known as ‘polycistronic expression’.

I had to have this explained to me in simple terms. Essentially, however, genes tend to be expressed when they’re needed (not always, but often), and are “turned on” or “turned off” in different places and at different times, especially in eukaryotes like us. This happens before the genes are transcribed by cells (most of the time).

Kinetoplastids, however, have highly conserved genes present in big blocks that are all transcribed whether they’re needed or not. The regulation of these genes then happens after they’ve been read rather than before.

This is so weird for eukaryotes that it is thought that this might be a very primitive form of gene expression, especially as this is more like how bacteria express genes, which exist as ‘operons’ - conjoined blocks of DNA that code for whole processes.

Polycistronic expression is weird, but it’s also very useful for studying evolution, as the blocks of genes can be highly conserved. This means that it’s relatively easy, if we know what blocks of genes are present in related species, to spot where one is missing. In this way we are able to look at the differences and ask how these came to be in different conditions.

One such interesting question, for example, is how trypanosomes came to be parasitic, compared to a close relative, Bodo saltans, which lives freely. It’s also interesting to compare parasites with non-parasites, as the former sometimes appear to have lost metabolic pathways, such as sugar metabolism, after their long history living within their hosts, who now do much of the work for them.