Raise your PAWs to celebrate the hard work of postdocs

This week is Postdoc Appreciation Week (PAW) - a celebration of the vast - and often under-recognised - contribution postdocs make towards both research and academic life in general.

It’s an absolutely crucial role in any lab, balancing research, teaching, training others, and learning. But the contributions made by postdocs to an institute’s science, innovation, and culture are often under-recognised.

Postdoc Appreciation Week (PAW) is designed to remedy that - a celebration of the vast contribution postdocs make, towards both research and academic life in general.

Life as a postdoc is widely seen as a route to a full-time research position. In reality, only a handful of PhD graduates go on to become members of faculty or run their own group.

The rest follow very diverse paths. They can continue to follow their interests as postdocs in a research group, train as specialised technicians or support scientists, parlay their research interests into a business, or move out of academia altogether.

We spoke to four researchers at the Earlham Institute to hear their views on what it means to be a postdoc.

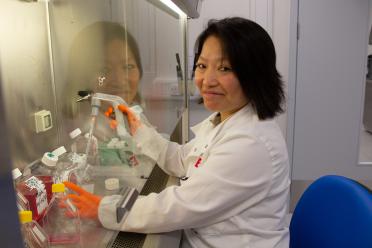

Angela Man is a Senior Postdoctoral Research Scientist in the Nieduszynski Group, working on replication errors in highly repetitive DNA sequences. She has previously worked around the UK in areas including plant molecular biology, cell biology, and immunology, gaining a diverse set of skills and interests along the way.

“Every day is different,” Dr Man says. “It’s not just a question of working in a lab, it’s about learning new skills and updating old ones.

“You can end up working very long hours - under some circumstances, the work requires it - but when you are invested in and passionate about a project it doesn’t seem like so much of a hardship because you are personally interested in what the outcome is.”

She says industry-wide views around what a postdoc does, and what the job means in terms of a career, can be limiting.

“Certainly, when I first started working, there was a very rigid career path. Your postdoc led to a fellowship, then fellowship to group leader. And if you decided not to follow that path, or you weren’t able to for various reasons, there was a tendency for people to not quite understand what you were doing.”

In a previous job, Dr Man was offered a promotion which could have led to more traditional career progression, but she decided not to take it.

“That promotion would have involved more admin and I didn’t want that,” she says. “I wanted to continue working at the bench. That was what I enjoyed.”

Every day is different, it’s not just a question of working in a lab, it’s about learning new skills and updating old ones.

Connor Tansley is a Postdoctoral Scientist in the Patron Group. His current project uses molecular biology to explore pharmaceutically interesting natural products in Nicotiana.

He says one of the major attractions of academic life was having the ability to make his own decisions about how to solve questions.

“I wanted to go down the academic route because of the greater creative freedom,” he explains. “In a job or grant application we choose a question to answer, and we can consider how we want to go about answering it - what the method will be.

“And that is where this can be a very creative and engaging job. You are constantly learning and growing as a postdoc - new techniques, new equipment.”

A postdoc can be an opportunity to develop independence, hone technical skills, and focus research interests. Postdocs’ experience means they often do the hard work that makes a project successful.

They also train and mentor graduate students and undergraduates, as well as doing the routine work that keeps a lab running smoothly.

Camilla Ryan, Postdoctoral Research Scientist in the De Vega Group, specialises in bioinformatics, data analysis, and coding.

She says passion for the project and a desire to constantly keep learning are both essential.

“If you’re lucky, you get to come to work and spend time on a project you’re passionate about and interested in. Essentially, you get paid to learn.”

As well as her own learning, Camilla has valued the opportunity to train the next generation. “The most fulfilling part of my job has been supporting PhD students in my group.”

And that is where this can be a very creative and engaging job. You are constantly learning and growing as a postdoc - new techniques, new equipment.

Darren Heavens, Senior Postdoctoral Scientist in Dr Richard Leggett’s lab, had a less traditional route into academia.

He worked in a number of roles involving genomics – for a pig breeding company investigating litter size and coat colour, for a start up company working on metabolic diseases such as diabetes, and on human cancer genomics.

He came to the Earlham Institute to work on plants, microbes, and animals, before he was made aware the University of East Anglia (UEA) offers a PhD by publication. This is an award intended for people with significant experience in a specific research area who have made a substantial contribution to the discipline via published papers.

Dr Heavens says that, although UEA offers the qualification, nobody on the Norwich Research Park had registered for at least five years. “Although it was time-consuming to complete all the paperwork, it was great to have the support of the Institute and the Graduate Studies Office.

“Now I’ve completed, I’ve been pleased to see a number of people at the Earlham Institute realise it’s available to them and do the same. It has certainly helped me pursue the research career I wanted.

“However, I don’t feel it’s essential to have a PhD to be able to do the work we do – there are some people I work with who are absolutely brilliant at their jobs and have not taken that route who would be more than capable.”

Dr Heavens works across several areas, getting the chance to participate in both research and teaching. Like Dr Man, he says one of the attractions is the variety of work.

“One day I will be working on detecting plant pathogens in crops,” he says. “The next I will be over at the hospital working on a project to detect antimicrobial resistance genes in neonatal faecal samples.”

It’s more acknowledged that science is a team effort. This is where initiatives like the Institute joining the Technician Commitment come in. It’s refreshing and positive to see that.

There can be disadvantages, however, to postdoc roles. All four of our postdocs agreed that pay and job security is an industry-wide issue.

Throughout the sciences, contracts for postdocs are mostly temporary - between one to three years - and often involve moving hundreds of miles, if not changing countries.

“It’s hard if you have other responsibilities,” Dr Tansley says. “If you have a partner or caring responsibilities, or if you are thinking about settling down and getting a house, it’s very difficult having to uproot yourself and others.”

And Dr Heavens says the short length of contracts is a disadvantage not just for postdocs themselves, but for science in general.

“You can have someone who is really experienced and a great asset to a group and then their contract expires and they may leave. You lose all of that knowledge. These are the people who would train up the new PhD students. It doesn’t allow for continuity.”

Dr Ryan agrees, saying: “The length of contracts means that you are constantly thinking about what happens when your current contract is over.

“For example, on a three-year contract, you might spend the last three or four months applying for other jobs - that’s time which could be spent on research.”

While Dr Man says she has had to turn interesting jobs down because of short contracts, she sees Postdoc Appreciation Week and similar initiatives as signs of a more positive attitude to come.

“I think the idea that a PhD doesn’t mean you have to follow the traditional path is more accepted now,” she says.

“It’s more acknowledged that science is a team effort. This is where initiatives like the Earlham Institute joining the Technician Commitment come in. It’s refreshing and positive to see that.”

This year’s Postdoc Appreciation Week is running from Monday 18 September to Friday 22 September.

Originally an initiative from the National Postdoc Association in the USA, it is now also celebrated here, with the first ever British and Irish-wide events organised in 2020.