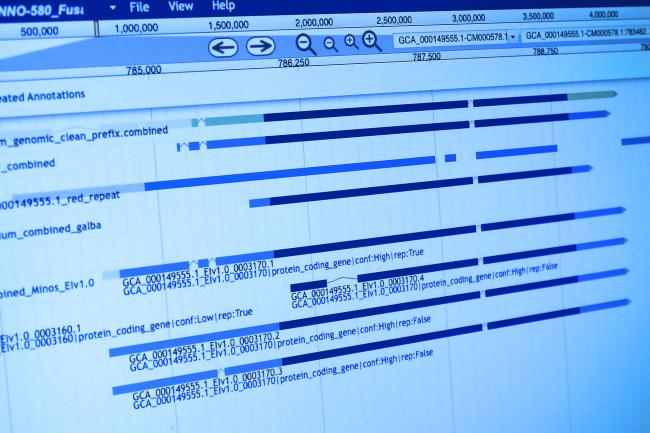

Crop pathogens can seriously damage food security. Why does crop disease spread so rapidly in agriculture? Population & Evolutionary Biologist Mark McMullan in the Plant & Microbial Genomics Group at EI explains the co-evolution of crop pathogens.

Global crop production is under constant threat from extreme weather events such as drought, as well as infestation by insects and microorganisms. There is no evidence to suggest that these problems will just go away. Furthermore, global population growth and climate change are likely to exacerbate the situation.

I am interested in understanding how the forces of evolution (e.g. natural selection, recombination and genetic drift) come together to allow pathogens to adapt and infect their host, and in turn the hosts also adapt to try and ‘keep up’.

Moving targets

This co-evolution is particularly interesting within an agricultural setting where massive monocultures of crops change the dynamic and ‘move the goalposts’ compared to the normal situation in a wild setting.

This means that once a pathogen gets the advantage it can be very successful and sweep across entire crop populations. This change in the dynamics within agricultural co-evolution doesn’t just change how selection works on novel pathogen mutants, it is believed also to be able to change the way pathogens reproduce.

Ordinarily, natural selection of pathogens is thought to operate to make the pathogen a ‘moving target’ to the plant, so that it’s difficult for the host plant to defend itself. This interaction between a pathogen species and a plant species is therefore very specific (co-evolution).

The question “why have sex?” is one that has been puzzling biologists for some time.

Bad sex

Sex between pathogens that infect different host plant species has generally been thought of as bad (for the pathogen progeny) because it reduces the specificity between the pathogen and the plant, and could allow the host plant to detect the pathogen.

However, research I have recently published in eLife with the Jonathan Jones’ group at The Sainsbury Laboratory shows that a species of pathogen does just that.

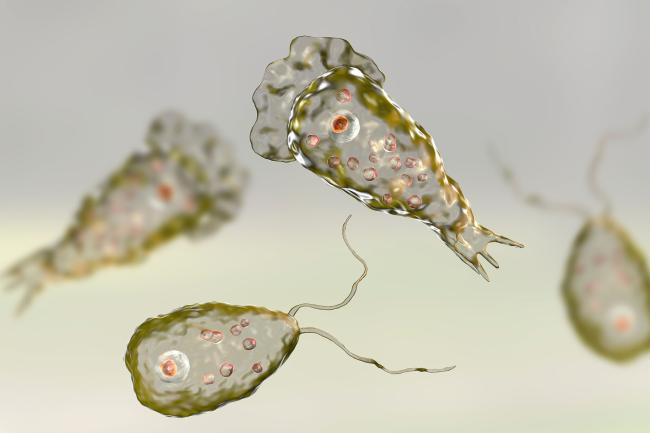

A single species of oomycete (Albugo candida), a plant pathogen that looks like a fungus but is only distantly related, can infect numerous host plant species.

With this plant pathogen, each race is specialised to its specific plant host. However, the genomes of these specialised races tell us that very occasionally they cross with another race that is specialised to a different host plant.

Sex and introgression

Sex between species is called introgression and these introgression events have been known to science for quite a long time. The advantages to an individual of a species of acquiring a new ability, perhaps to be able to process a new metabolite, are quite easy to envisage.

The difficulty in the case of Albugo candida, however, is that it is believed that the genes involved in attacking a plant are part of the specific interaction of that pathogen and its host.

On our oomycete, Albugo candida, we see that these introgression events have occurred between different races but as yet we haven’t observed that some genes (or regions of the genome) cross the race boundary more readily than others.

The idea that useful genes can also come from a pathogen that is adapted to attack a different host species and, that this could happen multiple times, will require some thought and a lot more investigation. Agathe Jouet a PhD student at The Sainsbury Laboratory is now exploring this phenomenon using a larger population experiment.

… we have found that a little bit of sex with something quite different could be advantageous …

Sweet spot

Finally, this leads us to think about the importance of sex between individuals of a species. In science it is often important to ask what might seem like very simple, even stupid questions. After you ask them though (e.g. “what is mass”) finding the answer can prove quite difficult.

The question “why have sex” is one of those questions that has been puzzling biologists for some time. There are lots of advantages to having sex but there are also disadvantages.

Here, we have found that a little bit of sex with something quite different could be advantageous but we are still to identify exactly what those advantages are, particularly in relation to crop pathogens.

Moreover, the ‘sweet spot’ between sexual and asexual (or clonal) reproduction could be a particularly interesting area of host pathogen co-evolution in agricultural systems.