Research from the Earlham Institute, Quadram Institute, and University of East Anglia suggests low protein diets disrupt or shield against some of the infection machinery deployed by salmonella.

While the study can’t provide dietary advice, it does reveal new insights into the link between dietary protein and innate immunity, as well as new avenues for further research.

Western diets, which tend to be high in ultra processed foods and animal protein, have been linked to an increased risk of developing metabolic and liver diseases. But little is known about the influence of dietary protein on immunity.

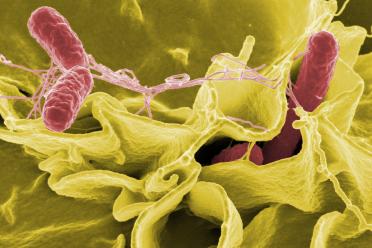

To explore the relationship, the researchers investigated the impact of reduction of dietary protein on a host’s response to salmonella infection in mice and on human immune cells found in blood.

The first experiment involved two groups of mice - one on a ‘normal’ diet and the other on a calorie-matched, low-protein diet. The second experiment studied human macrophages grown in an environment with low levels of protein.

Macrophages are a type of white blood cell that serve as our body’s first line of defence against pathogens by engulfing and "digesting" harmful microorganisms. They also regulate inflammation by producing antimicrobial proteins, helping to slow the spread of bacteria. However, this often causes damage to surrounding tissue.

Inflammation was induced in both the mice and the human macrophages and the immune response was tracked using advanced sequencing techniques, revealing the activity of different genes.

The researchers found the low-protein diet offered a protective benefit, particularly against liver damage caused by infection. By adding the amino acid leucine, they were also able to capture the impact of switching to a ‘normal’ diet.

Dr Edyta Wojtowicz, Group Leader at the Earlham Institute, said: “We wanted to understand how a low-protein diet affects our immune response to food-borne pathogens and inflammation.

“We found it protected mouse liver function and enhanced immunity by reprogramming the macrophages.”

“We saw two effects. At the molecular level, the low protein diet adjusted the macrophage's ability to damage surrounding healthy cells by releasing lower amounts of antimicrobial protein.”

She said the macrophages also became “hungrier” for pathogens and engulfed more of them as part of the evolutionary conserved process of autophagy, a physiological activity which enables cells to ‘recycle’ parts of ‘used’ cell components into new molecules.

“Excitingly, our initial tests on human macrophages – key immune cells – showed similar results.”

This work was partly delivered by the Earlham Institute’s Transformative Genomics National Bioscience Research Infrastructure and forms part of the work on somatic variation in healthy organisms within the Cellular Genomics strategic research programme.

Dr Naiara Beraza, Group Leader at the Quadram Institute, said “We know that Western diets increase the risk of developing metabolic conditions and liver disease. Our new results support the idea that components of our diet can affect the fitness of the immune system.”

“It’s intriguing to think that dietary changes might help us fight off infections, but so far we have only looked at one specific dietary pattern and we don’t know how longer-term changes might impact on immunity.”

As similar effects were seen in both mice and human immune cells, the researchers believe there is an opportunity for future research exploring dietary interventions during infection.

Dr Beraza added: “Overall, reduced levels of protein seems to boost macrophages' ability to engulf and destroy bacteria, while also reducing their production of inflammation-causing compounds, hence protecting liver function during infection.

She said this link between nutrition and immune function suggests the benefits of a low-protein diet on immune function may extend to humans, opening new avenues for nutritional approaches to boost immunity and combat infections.

“While these are exciting results, and open interesting possibilities for future research, they are preliminary and should not be used as dietary advice.”

The study 'low protein diet protects the liver from Salmonella Typhimurium-mediated injury by modulating the mTOR/autophagy axis in macrophages' is published in the journal Communications Biology, a Nature portfolio journal, and was funded by Wellcome, and UKRI Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Medical Research Council, as well as receiving support through the Norwich Research Park-wide Grand Challenges Fund.