This unprecedented milestone is marked with a collection of papers published today in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science, describing the goals, achievements to date, and future plans of the largest coordinated effort in the history of biology.

Confronting the climate crisis and protecting our natural world’s undervalued biodiversity, the EBP was launched in 2018 to provide a complete DNA sequence catalogue of 1.8 million species of plants, animals, fungi and protists - covering the vast majority of species identified to date worldwide.

Without action to curb climate change and protect the health of global ecosystems, Earth is forecast to lose 50 per cent of its biodiversity by the end of this century.

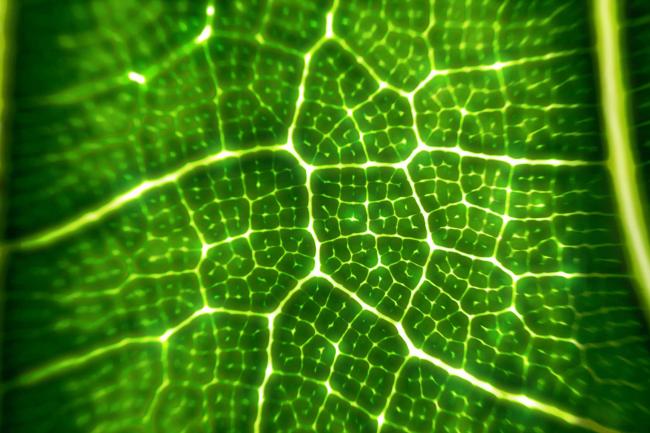

Creating a digital library of DNA sequences for all known eukaryotic life can help generate effective tools for preventing biodiversity loss and pathogen spread, monitoring and protecting ecosystems, and enhancing ecosystem services.

Funded by the Wellcome Trust, the UK arm of the EBP project - the Darwin Tree of Life project (DToL) - is being led by the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge with partners across the UK. At the forefront of this global effort, DToL aims to sequence genomes for around 70,000 species in Britain and Ireland, having submitted over 200 complete reference genomes to public databases in its first two years. Earlham Institute is one of the partners based in Norwich, leading on Protist species.

Director of the Earlham Institute, Professor Neil Hall, explains the project will push forward advanced genomic pipelines and data tools to discover the diversity of the UK’s unique natural history and ecological science: "The DToL project will provide a dataset at an unparalleled scale, providing invaluable insights into the biodiversity of the British Isles and its rich demographic and evolutionary history.

“Nature provides us with some of our most valuable resources and assets - from medicines and materials to our natural landscapes. The genomics information we generate and document will not only help us preserve nature but also help us harness its power, elevating our natural world and unearthing possibilities to reveal its true potential.

“Here at EI, our leading expertise in single-cell genomics and bioinformatics is developing data pipelines to ensure the DToL community can sequence and analyse novel organisms by generating shareable and reproducible data - maximising efficiency and collaborative research impact.”

The goal for phase one of EBP, which runs until 2023, is to produce reference genomes representing around 9,400 taxonomic families. So far, affiliated projects1 have produced about 300 such reference genomes, with the majority of these coming from the Darwin Tree of Life project.

These genomes range from species such as the Eurasian water vole, which is at risk of disappearing from Britain and Ireland, to the kākāpō, a parrot endemic to New Zealand that is at risk of extinction2. Other key families in the pipeline include those providing invaluable ecosystem services, such as bees and earthworms.

With the groundwork done on EBP and affiliated projects, 2022 will see activity ramp up considerably. EBP expects 3,000 genomes to be sequenced in the year ahead, with DToL aiming to sequence and publish at least 2,000 reference genomes by the end of 2022.

Professor Mark Blaxter, Director of the Tree of Life programme at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “As climate change, globalisation of trade, and the degradation of agricultural and natural habitats drive the sixth mass extinction, it has never been more important to catalogue and understand the biodiversity of our planet. Openly accessible understanding of species’ biology is a global good.”

The first phase of DToL has been successful in laying the foundation to move from sequencing a handful of species to sequencing all species in Britain and Ireland. This has required close collaboration between diverse communities of researchers with expertise in biodiversity, sequencing, genomics, and analysis. The result is an end-to-end process that assures integrity, accuracy, and quality in the genomes produced, capable of scaling up to sequence many thousands more by 2030.

Professor Ian Barnes, Principal Investigator for the Darwin Tree of Life Project at the Natural History Museum, said: “For over a century, the Natural History Museum has collected species from across Britain and Ireland, and made those specimens available for visiting scientists and the public, to better understand the natural world. Now, with a team of universities, museums, botanic gardens and many other naturalists, we are using that expertise to find, identify and deliver specimens for genome sequencing, at a massive scale, for anyone in the world to work with.”

Michelle Hart, from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, said: “Centuries of natural history research have created a uniquely rich knowledge base on the diversity and ecology of the plants, animal and fungi of Britain and Ireland. This is a perfect system for deploying massive scale genome sequencing of all species to give unprecedented and transformative insights into the nature of biodiversity and how it functions.”

Harris Lewin, chair of the EBP Working Group and Distinguished Professor of Evolution and Ecology at the University of California, Davis, said: “The special feature on the EBP captures the essence and excitement of the largest-scale coordinated effort in the history of biology. From fundamental science to breakthrough applications across a wide range of pressing global problems, such as preventing biodiversity loss and adapting food crops to climate change, the EBP’s progress in sequencing eukaryotic life is humbling and inspiring. Achieving the ultimate goal of sequencing all eukaryotic life now seems within our reach.”