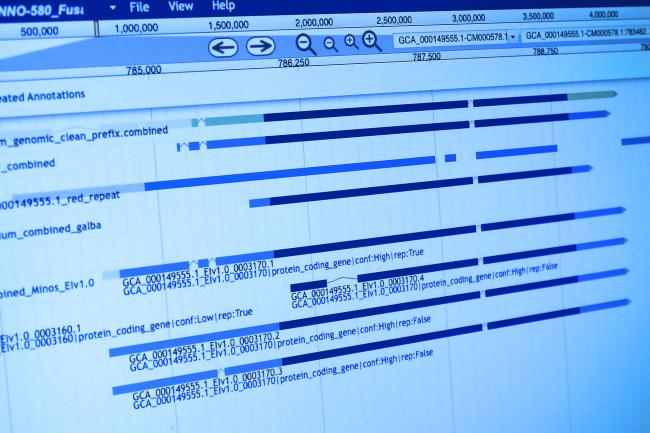

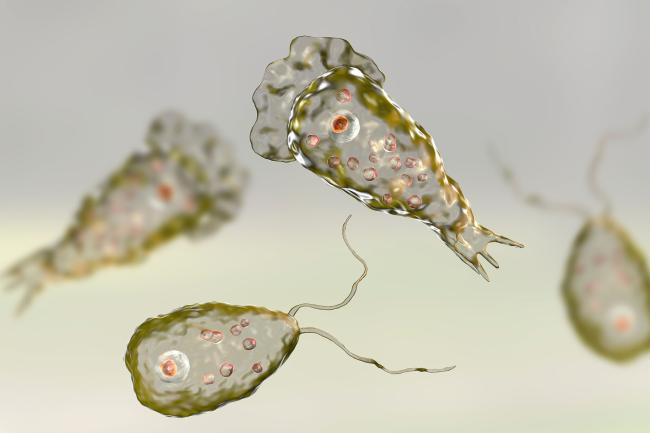

Led by Drs John Postlethwait and Ingo Braasch from the Institute of Neuroscience, University of Oregon, US, in collaboration with The Earlham Institute (EI), the study of the Spotted Gar (Lepisosteusoculatus) genome reveals that it is small and manageable. Furthermore, it lacks much shuffling and duplication that occurred in the ‘main’ fish ancestral line; it conserved its genome.

The Gar is particularly useful for biological studies because it bridges the gap between most fish and other vertebrates, allowing much more meaningful comparison than before. Its genome resembles the common ancestor of fish and four-limbed animals, such as birds. Indeed, the Gar’s chromosomes show only 17 major rearrangements from the chicken’s, despite the evolutionary gap between them.

Prof Di Palma, co-author of the study and Director of Science at EI, said: “The Spotted Gar is a superb reference species, an out-group that provides additional statistical power to help define much of the functional material in vertebrate genomes that otherwise remains obscure.”

Around 96 per cent of all known fish species are categorised as Teleosts (ray fins). The Gar belongs within the other four per cent and provides a highly informative comparative basis for evolutionary studies. For example, researchers have already used the Gar genome to find the genetic equivalent of wrist/ankle/digits in this living fish, confirming fossil evidence of an aquatic origin of fin-to-limb transition (1).

The Gar branched off from the Teleosts more than three hundred million years ago and conserved its genome more than might be expected since then. So far, we only know of one fish species that may have evolved more slowly – the coelacanth, often referred to as a ‘living fossil’.

To a casual observer, the Gar largely resembles a typical fish – but it does have rather unusual ‘ganoid’ scales, with a primitive sort of enamel for strength. Its genome sequence has two genes involved in mineralisation of enamels for those scales – evidence that ‘enamel genes’ evolved in early vertebrates before they were recruited to teeth. Teleost fish, by contrast, lack those enamel genes; only the Gar provides the clues for sorting out the evolutionary tree for that gene family (2).

Prof Di Palma, added: “The Gar genome clarifies the evolutionary history of many important gene families, including numerous ancestral noncoding elements.”

Prof John Postlethwait, commented: “Especially important for understanding human health and disease, the gar genome helps identify genetic sequences that are shared by human disease genes and teleost fish medical models like zebrafish; by studying those otherwise invisible shared elements, we will be able to better understand human complex diseases like diabetes, heart disease, addiction, and the bone loss that comes with ageing. ”

The scientific paper, titled: “The spotted gar genome illuminates vertebrate evolution and facilitates human-to-teleost comparisons” is published in Nature Genetics.