Five Earlham Institute technologies you should be using

The Earlham Institute is home to cutting-edge technology platforms, software tools, and talented people with the expertise to ensure we maximise the potential of these resources.

Our scientists, technicians, and platform managers oversee the wider infrastructure that drives data-intensive bioscience and technology development at the Institute. Thanks to our strategic funding from UKRI-BBSRC, both the on-site equipment and software we’ve developed are available to you.

Whether you’re looking for the latest single-cell platforms, want to scale up your science, or need software that produces metagenomic data from sequencing runs in real-time, we have a selection of technologies you should be accessing.

The Leica LMD7 Laser Microdissection microscope acts as an incredibly precise scalpel, using a laser to cut out and isolate single cells or perform a microbiopsy on your tissue of interest.

The Institute’s Cellular Genomics Platform Manager Andy Goldson says: “This is a very precise method for getting exactly what you want out of a very small area.

“It can chop a single cell out of a leaf or remove organelles out of cells – it works right down to the level of chromosomes. You can pinpoint exactly what you want.”

He said the level of precision available meant it was very popular with botanists and researchers who were working on the spatial relationships between cells.

“It works very well on fragile or difficult to isolate cells, and it’s a great method of obtaining spatial information about cells that you otherwise would not be able to have.”

The Leica LMD7 Laser Microdissection microscope

Housed within the Institute’s Spatial and Single-Cell Analysis lab is a cell sorting capillary instrument, comparable with a flow cytometer - the Cellenion cellenONE F1.4.

The CellenONE offers cell sorting and imaging, compatible with very large and very small cells. It can isolate tens to hundreds of single cells for in-depth sequencing or culture.

“This machine works on a similar principle to flow cytometry,” explains Dr Goldson, “but without the high pressure.

“It’s as precise, but much gentler. This makes it extremely good for delicate or rare cells.”

The machine can also capture an image of the cells passing through it, so visual inspection of samples is possible even while they are being processed.

The Cellenion cellenONE F1.4

The Earlham Biofoundry can provide platforms and expertise in large-scale experiment design, scale-up, and automation.

For example, the BioLector is an automated platform for small-scale fermentation, allowing fermentation of very small volumes (less than 2ml) for rapid assessment of strain behaviour and performance under various cultivation conditions.

Earlham Biofoundry Manager Dr Carolina Grandellis says: “Fermenters usually operate at high capacities – 25 or 30 litres. If your culture is not behaving in the way you want, this can lead to a lot of waste.

“The BioLector is a very effective screening tool. You can grow 48 samples in parallel, specifying different conditions and media, and you can monitor levels of oxygen, pH, or fluorescence.”

After this has been done, it’s easy to select the recipe with the best performance according to your requirements, which is used to inform full-scale operation.

The Institute can set up use of the BioLector in several different ways. “We can offer a collaborative process,” says Dr Grandellis, “or a service where we run the samples and report back the results.

“We can train people to use it, or they can hire it and use it with our support.”

The BioLector - an automated platform for both aerobic and anaerobic micro-fermentation

The Earlham Biofoundry houses four Opentrons lab robots, which are designed to automate repetitive lab pipetting tasks.

“The Opentrons can complete arduous pipetting tasks that would otherwise have to be done by hand,” explains Dr Grandellis.

“It allows you to automate anything from aliquoting media to whole DNA preps, setting up PCRs, or cherry-picking from a spreadsheet as input - with high accuracy - making the process much easier and less repetitive.

“They can even work with different solutions in the same run - anything from five microlitres to a millilitre.”

The Opentrons software is open source and user friendly. For example, the software notices if the volumes will not be sufficient and asks you to change the protocol before running it.

Dr Grandellis says the machines are intuitive and easy to use. “We offer training and it takes less than half an hour to learn how to use them.”

The OpenTrons, open-source, easy-to-program automation platform

As well as offering access to technology platforms, the Earlham Institute develops software.

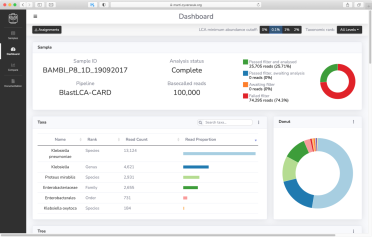

A good example is MARTi (Metagenomic Analysis in Real Time), an open-source software tool that enables rapid species identification, antimicrobial resistance gene detection, and a visualisation of results that updates automatically while the sequencing run is ongoing.

Dr Ned Peel, one of the developers of the tool, explains that MARTi allows users to taxonomically classify reads straight away, rather than waiting until the end of the run to start analysis.

“This could be very useful in situations where a quick identification is essential,” he says. “For example, if we are looking at an infection where time is of the essence.”

MARTi has two components: the MARTi Engine, which analyses the sequencing data and can be installed on either a local machine, such as a desktop or laptop, or a high-performance computing cluster; and the MARTi GUI (graphical user interface), a web-based tool allowing users to view and compare results, as well as generate graphs and figures for scientific publications and presentations.

MARTi is highly customisable and users can tune parameters and databases to the needs of their particular research.

Paired with the MinION, a portable DNA sequencer, MARTi can be deployed in the field alongside sample collection, running on a standard laptop without an internet connection.

MARTi is available through GitHub. A demonstration server can also be found online.

An example screenshot from a study using MARTi