Optimising the extraction of High Molecular Weight DNA from fungi

Sequencing an organism’s genome requires high-quality and high molecular weight DNA - but extracting fungal DNA of the necessary standard is anything but simple.

This article is part of our technical series, designed to provide the bioscience community with in-depth knowledge and insight from experts working at the Earlham Institute.

Michelle Grey is a Research Assistant in the Neil Hall Group. She works on projects related to pathogen infection of agricultural crops, such as wheat and beet.

Michelle has developed two methods for extracting high-quality DNA from fungi, both with different applications. Her full protocol is published on bio.protocol, but she has given us some insights and tips in this companion technical blog.

Growing demand for long-read data has come from its ability to span repetitive regions of the genome - improving assembly contiguity and the incorporation of repetitive content. However, producing suitable sequencing data for long reads is dependent on high molecular weight (HMW) DNA.

Fungi are notoriously challenging when it comes to DNA extraction. The challenge is to extract high concentrations of DNA while preserving strand lengths and integrity. Difficulties could be due to factors such as the presence of fungal cell walls, production of secondary metabolites, and typically small quantities of starting material.

I collaborated with scientists at Rothamsted Research to modify protocols from two commercial high molecular weight (HMW) DNA extraction kits to address these challenges.

This process extended over a year due to various complications - including the global pandemic - but ultimately our collective efforts led to the optimisation of two extraction method kits, the Cytiva Nucleon PhytoPure and the Macherey-Nagel NucleoBond kit.

And once we had the DNA, Naomi Irish from the Earlham Institute’s Technical Genomics team, was able to work her magic with the Institute’s HiFi PacBio platform to give us successful samples.

In this blog, I’m going to walk you through some tips, pain points, and adaptations of the methodology.

The full protocol that accompanies this blog can be found on bio.protocol.

Fungal cell walls are made from a material called chitin.

Chitin is a nitrogen-containing polysaccharide, similar to cellulose. It is relatively resistant to degradation and this, in turn, makes it difficult to ‘break into’ the cells and release DNA using typical mechanical techniques such as lysis buffer and bead beating to disrupt cells .

Aggressive lysis approaches must be taken in order to release the nucleases during the lysis stage of the protocols. However, this can result in nicked or degraded DNA.

We found that grinding to the point that the material resembled talcum powder worked well with our tissues. I used a mortar and pestle and liquid nitrogen to get the samples to a fine grind (pictured below).

Secondary metabolites and fungal cell wall structures were the first challenge to overcome on the extractions. I found harvesting them before any dark pigment developed yielded cleaner extracts with higher strand integrity.

This pigmentation protects the fungi - it intertwines with the chitin and some studies have found it goes as far as intertwining with nucleic acids. This is very useful for the fungi but, for us, letting it build up will cause issues. Harvesting before this happens is the technique I use whenever possible.

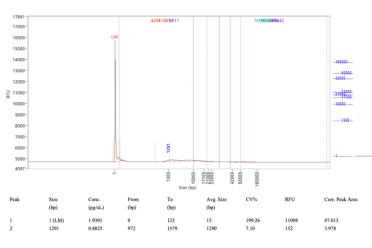

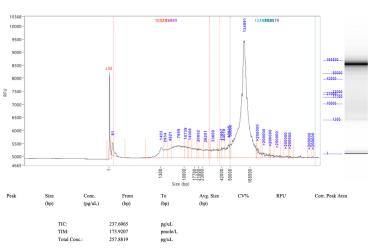

The next challenge was seeing high peaks of RNA contamination in the FEMTO traces. To overcome this, I kept adding higher amounts of the enzyme RNase A until these peaks were no longer there. This worked out to almost 10 times more for the Cytiva Phytopure kit.

Here you can see FEMTO traces taken from before I used the modifications (left) using the Cytiva kit and then traces after the modifications (right).

DNA integrity was another hurdle to jump.

I tried lower speeds on the centrifuge, shorter times on the centrifuge and spooling out the DNA by hand. These all improved the results, but not dramatically enough.

I had to slow down and go back to basics. Using wide-bore pipette tips for all the steps proceeding the lysis helped, so that would be my recommendation. Some of the samples successfully got through the PacBio sequencing with this. These tips worked in unison with the Cytiva Phytopure kit to provide successful sequencing runs and ultimately high quality genomes for some of our isolates.

Initially, we began processing with several methods but experienced the same problems with all of them - high degradation, contamination, and low yield.

After experimentation, we settled on the Cytiva and the Macherey-Nagel kits, both of which yield better than the other methods we were using but have different advantages.

The Cytiva kit is the best option we found for a limited amount of sample. For many fungi, lab culture is not possible and you are working with whatever you can get - sometimes tiny amounts.

However, if it is possible to bulk up your sample in the lab, it’s better to use the Macherey Nagel kit which uses a gravity-based approach rather than centrifuging and is much gentler on the strands.

I was introduced to this by one of the co-authors of my technical paper, Dr Jackie Freeman. I incorporated the tweaks to the method (described above)I had been using on the Cytiva kit on this new extraction kit, and also included a change at the extraction wash phase suggested by Dr Freeman (splitting the 5ml of eluted DNA into five 1ml tubes to be washed simultaneously).

This seemed to be what the trickier samples needed to get sequenced and I began to generate cleaner results with average strand lengths of 40kbp and up. I believe these results are most likely due to it being a gravity based method with little centrifuging. Huge thanks go to our collaborators at Rothamsted for introducing us to the Macherey-Nagel kit.

By now, we had submitted 21 samples for long-read sequencing. 18 of those successfully sequenced with some really good telomere to telomere assemblies.

The two methods: on the left a centrifuge used by the Cytiva Phytopure kit, and on the right the Macherey Nagel kit which uses a gravity-based approach which is much gentler on the strands.

I was asked to share my experience with the Darwin Tree of Life Fungal Group at the Wellcome Sanger Institute. They were reporting similar challenges as I had had in the extraction of high quality HMW DNA to long-read, whole genome sequence.

They had samples sent from all over the country and in varying amounts - some less than a gram - which made it very difficult for them to extract enough gDNA to sequence on a PacBio platform.

They were concerned about a number of difficulties - many of which I had faced, including the lack of DNA, contamination, low integrity numbers etc. Based on our experience, I encouraged the team to use the Cytiva kit and suggested they increase the RNase A treatments.

Although the results still seemed suboptimal I encouraged them to continue with sequencing as we had seen that some of our worst samples sequenced surprisingly well.

This was a difficult challenge. Quite possibly the most difficult thing I have ever done in science - but it was very rewarding. I have seven years’ experience working in the Designing Future Wheat (DFW) and Delivering Sustainable Wheat (DSW) programmes, and I have been working on this for two years. I have my techniques down and I now use the Macherey-Nagel method for samples we want to use PacBio whole genome sequencing on, and the Cytiva method for standard fungal extractions.

There have been improvements in the resin for the Cytiva kit, which seems to clean the samples better than before - although this may be down to me having control of the starting material now that I grow them up here in our lab - and DNA spooling is better. We have consistent results and it has been shared with other groups who were over the moon to have the two methods. I feel quite proud of it!

In 2022, I was able to submit several samples to our Technical Genomics group for PacBio long read sequencing, and most of them were successful in attaining high coverage and to near chromosome level. This has been a huge help to the wheat pathogen community, and was directly involved in the sequencing and genome assembly of Gaeumannomyces tritici, published by my colleague Dr Rowena Hill..

There is always room for improvement in science, and I will be continuing to polish my methods. I will also be working on other applications for these useful kits - they may have applications to our work on beet pathogens.

These protocols were developed with my colleague Dr Mark McMullan, in collaboration with Dr Kim Hammond-Kosack from Rothamsted Research. They are part of the cross-institute BBSRC research programme Delivering Sustainable Wheat.

Grey, M. J., Freeman, J., Rudd, J., Irish, N., Canning, G., Chancellor, T., Palma-Guerrero, J., Hill, R., Hall, N., Hammond-Kosack, K. E. and McMullan, M. (2025). Improved Extraction Methods to Isolate High Molecular Weight DNA From Magnaporthaceae and Other Grass Root Fungi for Long-Read Whole Genome Sequencing. Bio-protocol 15(6): e5245. DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.5245.

If you have any questions or feedback for Michelle please email communications@earlham.ac.uk.